Starting in the early 1600s, Colonial Virginia enacted the first Tobacco Inspection Act and warehouses officially launched a new type of commerce which stored, displayed, sold, and exported leaf tobacco. Because such operations were in business before the law was enacted, tobacco warehouses are considered the first American-born form of commerce.

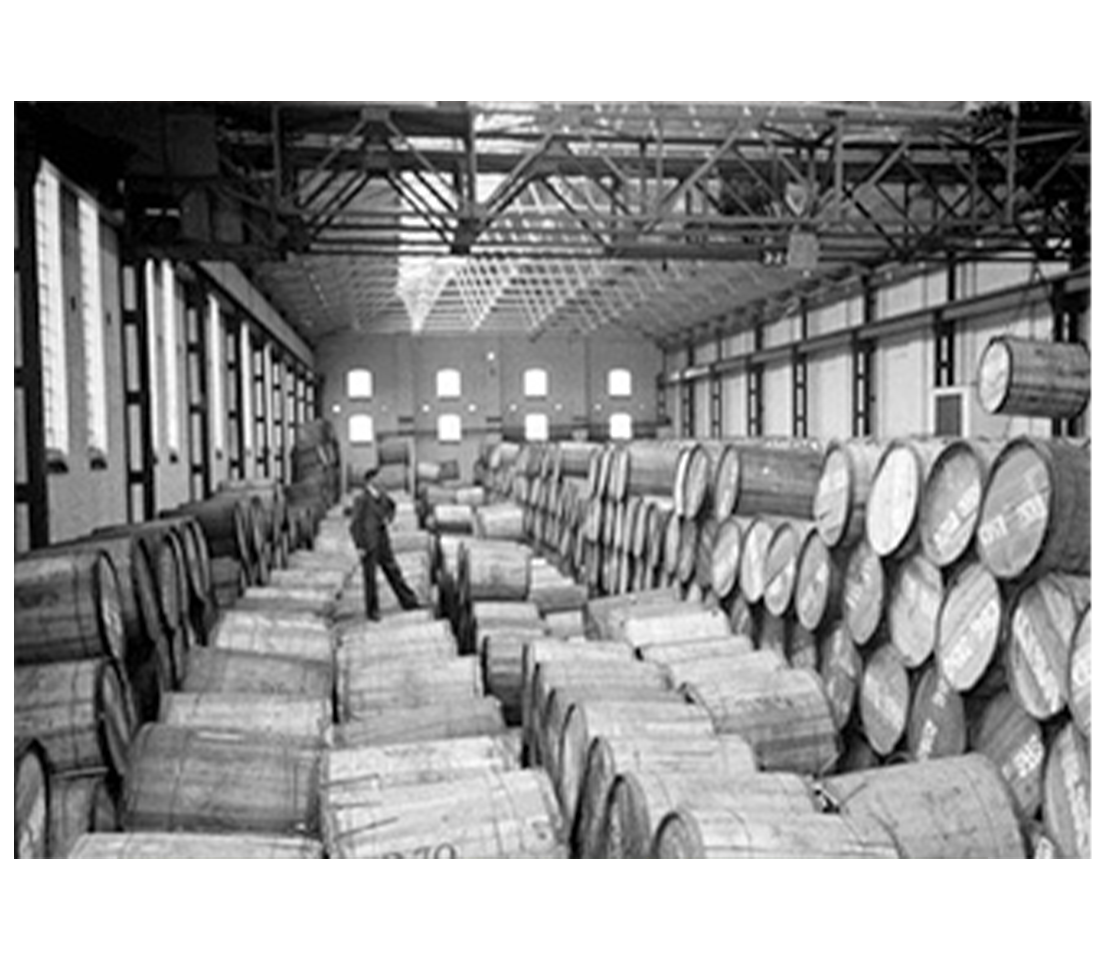

Early tobacco warehouses sprang up first in Virginia, but later in ever widening circles because they had to stay close to the farmers who supplied them. The key factor in this relationship was the tobacco hogshead- a wooden barrel into which farmers packed tobacco leaves they cured. An average hogshead weighed over one thousand pounds. Rural roads were primitive and animal power was the only available land transportation. So moving hogsheads from farms to warehouses presented real challenges to Colonial Americans.

To help tobacco growers meet these challenges, warehouse operators sought river locations close to clusters of large farms. To these riverbank warehouses, farmers could float hogsheads on flat boats. Similarly, buyers could use boats to send out hogsheads they had purchased.

The growth of America’s warehouse business formed centers around which towns and cities grew. The foremost of these early market centers was Richmond, Virginia. That market attracted tobacco farmers from all points of Virginia and North Carolina – the two states whose farmers dominated leaf production from the early 1600s until well after farmers began settling frontier territories to the west. Richmond would hold its prominence as North America’s leading tobacco warehouse center until the mid-19th century.

However, the future of tobacco production and warehouse operations were headed westward. Recognizing this trend, the Virginia Assembly established Kentucky’s first three tobacco warehouses in 1783, including one in Louisville. In 1788, North Carolina’s legislature created Tennessee’s first tobacco warehouse in Clarksville.

As had been the case along the East Coast, tobacco warehouses in frontier Kentucky and Tennessee “were at first crude log cabins. Appointed officials inspected the leaf, ordered any of inferior quality burned, and issued receipts for accepted tobacco.” Frontier growers created “tobacco roads” to many of these warehouses by rolling hogsheads which packed down the primitive dirt roads. Subsequently, more new towns sprang up alongside the riverbank warehouses and the hogshead formed roads leading to them.

In 1803, Thomas Jefferson – U.S. President and fellow tobacco grower – signed the agreement to purchase the Louisiana Territory from France. Once New Orleans became a secure conduit for the leaf trade, frontier warehouses proliferated. By 1810, there were 130 tobacco warehouses in Kentucky. By 1825, Louisville established itself as the region’s dominant hogshead warehouse market.

Meanwhile, down in North Carolina – where growers and warehouses had been overshadowed for nearly two centuries by the dominant Virginia tobacco trade – an 1838 discovery would, in time, revolutionize leaf tobacco production. The discovery by an African-American slave named Stephen altered the traditional ways of fire-curing dark-colored bright leaf tobaccos, that since the early 1600s had been known as “Virginia Leaf,” no matter where it had actually been produced. What Stephen did on a Caswell County farm in North Carolina was to use charcoal as the fuel for fire-curing. The new method created “flue-cured” tobacco – the plant class that, today, ranks as the world’s best selling leaf.

INTERESTING FACTS

- Pitt County is the largest flue-cured tobacco producing county in the U.S.

- In 1999, Pitt County sold 23,250,696 pounds of tobacco produced on 11,181 acres.

- In 2000, there were 31 sets of USDA graders and 49 tobacco markets in the U.S.

- In 2000, 80.5% of tobacco sold was classified to be “mature, ripe, and mellow”. This was the highest percentage in this category since 1974.

- Tobacco represents 14% of the total cash crop value in North Carolina.

- There are approximately 12,000 tobacco farmers in North Carolina and about 80,000 allotment holders. 16,000 workers are involved in processing, manufacturing, wholesale and retail outlets, and related industries.

- In 1950, the U.S. produced 25% of the world’s flue-cured production. In 2000, that figure is expected to be 6%.

- Tobacco is #7 in terms of cash value among agricultural commodities in the U.S. In terms of economic returns, it would take seven acres of cotton to replace one acre of tobacco.

- In tobacco, the top six producing states have 94% of production. Tobacco is produced in 16 states and in 568 tobacco producing counties in the U.S.

- Tobacco growing requires about 250 man hours of labor per acre harvested. By comparison, it takes about three man hours to grow and harvest an acre of wheat.

- In total, tobacco directly and indirectly employs 2.3 million Americans.

- Approximately 1 out of every 11 workers in North Carolina depends on tobacco for his or her livelihood. Tobacco directly and indirectly provides jobs for more than 280,000 North Carolinians.

- North Carolina produces more than 40% of all tobacco grown in the U.S. and 60% of all flue-cured tobacco.

- In terms of alternative crops, there is no commodity in short supply that farmers can switch to and find a profitable market.

- Tobacco is the world’s leading non-food crop. It is grown in more than 100 countries.

- Tobacco accounts for 5% of the state’s gross product, or about $11 billion. It ranks second to textiles among North Carolina industries.